Heat Sink Technology: How Fins and Materials Maximize Cooling

In the fast-paced world of high-performance electronics and machinery, one silent threat looms large: excessive heat. Unchecked, it can cripple performance, drastically cut lifespan, and even trigger catastrophic failures. This is where heat sinks step in; these clever passive devices act as vital thermal bridges, expertly moving heat from sizzling components to a cooler environment. Today, we’re diving deep into what makes a heat sink truly effective: the clever engineering of its fins and the smart choice of materials.

The Science Behind Heat Sinks: Conduction and Convection

At its heart, a heat sink works through a two-step heat transfer dance: conduction and convection. First, heat flows directly, or conducts, from the scorching component (think your CPU or a power transistor) straight into the heat sink’s base. From there, it continues its journey, conducting through the heat sink’s main body and out to its extended surfaces – those distinctive fins. The ultimate goal? To shed as much heat as possible from these surfaces into the surrounding air through convection. While less prominent, radiation also contributes a bit, particularly when temperatures climb or with specific surface finishes.

The Role of Fins: Maximizing Surface Area for Convection

The fins are arguably the most eye-catching part of any heat sink, and their design is absolutely critical. Their primary job is straightforward: to dramatically boost the surface area available to dump heat into the ambient air. Simply put, more surface exposed means more heat can escape via convection. However, designing these fins is a delicate balancing act. Factors like their height, thickness, how far apart they’re spaced, and their overall shape directly influence how easily air can flow through them and, crucially, how efficiently they transfer heat. Pack too many fins too close together, and you risk choking off airflow, creating a ‘boundary layer’ of stagnant, warm air that actually hinders heat transfer instead of helping it.

| Fin Type | Key Characteristic | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|

| Extruded Fins | Straight, parallel fins; cost-effective for high volume. | CPUs, GPUs, power supplies |

| Skived Fins | Thin, high-density fins cut from a solid block; excellent performance. | High-power applications, servers |

| Pin Fins | Cylindrical or elliptical pins; omnidirectional airflow, lower pressure drop. | Compact electronics, where airflow direction is uncertain |

| Folded/Bonded Fins | Thin sheets of metal folded or bonded to a base; very high fin density. | High-performance computing, industrial electronics |

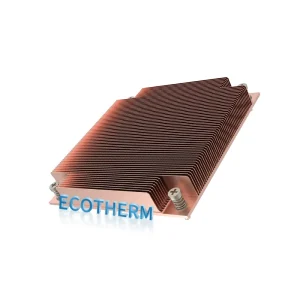

Material Matters: Choosing the Right Conductor

When choosing a heat sink material, everything boils down to its thermal conductivity – essentially, how good it is at letting heat pass through. The better the conductivity, the quicker heat can zip from the component, through the heat sink’s base, and out into those all-important fins. Most often, you’ll find heat sinks made from either aluminum or copper, each bringing its own set of advantages to the table.

Aluminum, particularly the 6063 alloy, reigns supreme as the most common heat sink material. It hits a sweet spot: decent thermal conductivity (around 205 W/m·K), low cost, lightweight, and incredibly easy to extrude into complex shapes. Copper, on the other hand, boasts truly impressive thermal conductivity (around 400 W/m·K). This makes it the go-to for high-performance setups where space is tight and you need every bit of heat dissipation you can get. The trade-off? Copper is heavier, pricier, and a tougher challenge to machine compared to aluminum. For cutting-edge applications, engineers are even exploring exotic materials like graphite or diamond composites for their unbelievable thermal properties, though they come with a significantly higher price tag.

“The synergy between advanced fin geometries and high-conductivity materials is what truly defines modern heat sink efficiency. It’s not just about more surface area, but about how effectively that surface area interacts with the thermal properties of the chosen metal.” — Dr. Anya Sharma, Lead Thermal Engineer at Apex Innovations

Advanced Heat Sink Technologies

But passive finned heat sinks are just the beginning; advanced thermal solutions often weave in additional clever technologies. Take heat pipes and vapor chambers, for instance. These brilliant devices use a phase-change fluid sealed within a vacuum to whisk heat away far more efficiently over greater distances, effectively extending the heat sink’s reach. You’ll often find them nestled within traditional finned heat sinks, working to spread heat evenly across the fins and turbocharge their convective potential. Then, for the most demanding applications, liquid cooling systems push the boundaries even further. They circulate a dedicated coolant directly over the sizzling component, before transferring that heat to a radiator, offering unparalleled thermal capacity.

Ultimately, getting the best performance from a heat sink is a fascinating and intricate engineering puzzle. It pulls together fluid dynamics, material science, and mechanical design. By thoughtfully crafting fin structures to maximize surface area for convection and picking materials that excel at conducting heat, engineers can deftly keep temperatures in check. This crucial work safeguards the reliability and boosts the performance of vital electronic and mechanical systems across countless industries, ensuring everything runs smoothly.

Frequently Asked Questions About Heat Sinks

The primary function of a heat sink is to transfer heat generated by electronic or mechanical components into a fluid medium (usually air) to dissipate it away from the component, preventing overheating and maintaining optimal operating temperatures.

Increased surface area, primarily provided by fins, allows for greater contact between the heat sink and the surrounding air. This larger contact area facilitates more efficient convective heat transfer, enabling the heat sink to dissipate heat more effectively.

Aluminum is commonly used due to its good thermal conductivity, low cost, lightweight, and ease of manufacturing (especially extrusion). Copper is used for high-performance applications because of its significantly higher thermal conductivity, although it is heavier and more expensive. Each material is chosen based on the specific application’s thermal requirements, cost constraints, and weight considerations.

Heat pipes enhance heat sink performance by using a phase-change process to rapidly transfer heat from a hot spot to cooler areas of the heat sink, often into the fins. This effectively spreads the heat more evenly across the entire fin structure, maximizing the efficiency of the convective heat transfer to the ambient air.